Psychosocial Treatment, Software Interventions, Part 1

Substance abuse negatively impacts public safety, reduces workers’ productivity, and contributes to higher health care costs, premature deaths, and disability for millions of Americans. Despite this massive health problem, only a fraction of affected people get the help they need. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health released in 2013 by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) showed that in 2013, 22.7 million people aged 12 or older (9.6% of the population) needed treatment for alcohol or drug problems, with only 2.5 million receiving help. Even fewer get the treatment that works the best. For those affected, Substance Use Disorder Treatment is crucial for effective recovery, emphasizing psychosocial interventions.

Psychosocial Treatment, Software Interventions

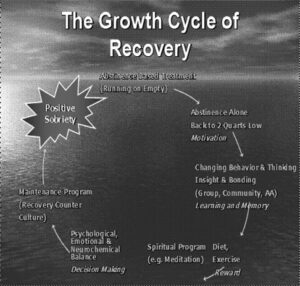

The addicted brain, struggling with deficits in reward, learning and memory, motivation, and decision making, requires a comprehensive treatment approach. Physical, psychosocial, spiritual, and, in many cases pharmacological, interventions are necessary in treating addicted individuals. The disease model of addiction has promoted a number of effective pharmacological approaches to addiction; however, nonpharmacotherapeutic interventions are necessary and ultimately the most effective for long-term recovery.

Most individuals in early recovery benefit from treatment along with a therapeutic community, the implementation of nonchemical coping skills, and the fellowship of Alcoholics Anonymous or other such groups. These interventions assist the addict in adopting more adaptive ways to create reward, improve decision making and motivation, and establish new memories. The nonpharmacotherapeutic strategies are powerful enough to create new connections between neurons, or neurogenesis. This can be likened to “software” approaches that change the hardware of the brain, as opposed to only looking at direct hardware approaches, like medication management or some form of neuromodulation, as mentioned previously. In many cases, however, the addict needs both. The path to recovery must be multifaceted to be successful.

Figure 2: The above figure outlines how the disease model informs and guides the treatment process, moving from abstinence to positive sobriety through changing behavior, thinking, relationships, lifestyle, and ultimately neuronal pathways. This also correlates to enhancements in reward, learning and memory, motivation, and decision making.

Our Treatment Structure

In the early1940s, attempts were made to have AA partner with treatment programs, such as Wilmer hospital in Minnesota. Eventually, AA recognized the need for separation from the treatment programs within hospital systems. However, the philosophy of AA became integrated into the treatment process, revolutionizing treatment approaches and outcomes for generations. Pioneer House was the first treatment program in Minnesota to base its three-week residential program on the philosophy of Alcoholics Anonymous. This was called the Minnesota Model (White 1998). The program pioneered a treatment approach that incorporated twelve-step principles and influences while maintaining autonomy and a degree of distance from AA. This model also embraced the concept that alcoholism is a disease, not a symptom of an underlying psychiatric illness.

Today, most abstinence-based programs like ours have evolved from this model and have become more inclusive of psychological and pharmacological strategies. This model also has a rich history of utilizing a holistic and integrative approach to alcoholism and other addictions. This approach centers on a multidisciplinary team that includes recovering alcoholics and integrates the tenets of AA into the treatment process. Since the AA program has an emphasis on the spiritual aspects of recovery, AA has become an essential element of holistic treatment. The Minnesota Model lends itself to recovery because of a legacy that began with the advent of twelve-step recovery programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous, which began in 1935 (Spicer 1993; Anderson 1981; Laundergan 1982). According to Damian McElrath, as described in the Journal of Psychoactive Drugs (1997), AA contributed the following to the Minnesota Model: 1) the knowledge or belief that alcohol is a physical, mental, and spiritual illness; 2) the idea that the twelve steps outline the problem, solution, and the spiritual exercises needed to live in the solution; and 3) the understanding that fellowship and recovery takes place with one alcoholic talking to another.

Khantzian and Mack (1994) have reinforced the importance of the psychosocial support of a therapeutic community in the treatment of addictions. They state, “Alcohol and drug dependence are the result of complex interactions of biological, psychological, and cultural factors; yet, the most promising and successful interventions in these disorders are psychosocial in nature.” Although AA and treatment separated rather early in the process, the connection between them remains vital for everyone who subscribes, in some form, to this model. Involvement in this model of treatment with aftercare and ongoing AA involvement has shown positive results (Project Match Research Group, 1997).

The structure of our program includes psychosocial support in a therapeutic community—that ability for support from other addicts and alcoholics within the framework of a day hospital setting—supplemented by a peer-supported independent living program (ILP). Our structure is derived from the Minnesota Model and one that Doug Talbott, MD, pioneered in the mid-1970s. The Talbott model is a four-month model that was primarily designed for the addicted health care professional. The first month was a residential experience after which the patient moved into independent living and spent a month in a day hospital setting then worked for the last two months as a health care professional in an addiction-related program in the community (e.g., Salvation Army Addiction Program) while remaining in the ILP. This last two months of step-down work was referred to as “placement,” which this manual explains later on.

Over the years here in Chicago, we have streamlined the program to be more economically feasible and individualized but to still have the necessary clinical impact. In our book Healing the Healer and in more recent outcome studies, we established that we had comparable outcomes to the longer Talbott program. If our patients need an inpatient stay, it is typically for detox and stabilization done in a typically briefer period of a few days. Our length of stay averages eight weeks, with our step-down phase using the volunteerism program and placing the patient in a more advanced role within our program instead of in practice as a health care professional outside of our setting. This allows us to have more contact with the patient and enables us to have this important placement phase available to our non-health care professionals. This structure is not for everyone, as some patients need longer stays in an extended residential setting. We try to individualize our recommendations for treatment and to avoid a one-size-fits-all mind-set.

The modalities described in this article delineate our treatment approach within the structure we embrace. That structure includes two to four weeks in a day hospital setting with most living in the ILP. Step-down, or “placement,” into the Intensive Outpatient (IOP) component following the patient’s time in the day hospital allows the patient to continue in the critical morning small group process and engagement in the larger therapeutic community while having more time in the afternoons for individual needs like volunteerism and individual therapy. Nightly AA meetings during the week and at least one meeting a day on weekends is required.